Thérèse of Lisieux

| Saint Thérèse of Lisieux | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux in the Carmelite Brown Scapular (1895) |

|

| Virgin and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | 2 January 1873 Alençon, France |

| Died | 30 September 1897 (aged 24) Lisieux, France |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 29 April 1923 by Pope Pius XI |

| Canonized | 17 May 1925 by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | Basilica of St. Thérèse in Lisieux, France |

| Feast | 1 October 3 October in General Roman Calendar 1927–1969 |

| Attributes | flowers |

| Patronage | AIDS sufferers; aviators; bodily ills; florists; illness; loss of parents; missionaries; tuberculosis; CatholicTV; Australia; France; Russia; Kisumu, Kenya; Witbank, South Africa; Anchorage, Alaska, U.S.; Fairbanks, Alaska, U.S.; Juneau, Alaska, U.S.; Cheyenne, Wyoming, U.S.; Fresno, California, U.S.; Pueblo, Colorado, U.S.; Massachusetts (U.S.); Lansdale Catholic High School, Lansdale, Pennsylvania, U.S.; Theresetta Catholic School, Castor, Alberta, Canada |

Thérèse of Lisieux (2 January 1873 – 30 September 1897), or Saint Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, born Marie-Françoise-Thérèse Martin, was a French Carmelite nun. She is also known as "The Little Flower of Jesus".

She felt an early call to religious life, and, overcoming various obstacles, in 1888 at the early age of 15, became a nun and joined two of her older sisters in the enclosed Carmelite community of Lisieux, Normandy. After nine years as a Carmelite religious, having fulfilled various offices, such as sacristan and novice mistress, and having spent the last eighteen months in Carmel in a night of faith, she died of tuberculosis at the age of 24. The impact of her posthumous publications, including her memoir The Story of a Soul, made her one of the greatest saints of the 20th century. Pope Pius XI called her the Star of his pontificate; she was beatified in 1923, and canonised in 1925. The speed of this process may be seen by comparison with that applied to a great heroine of Thérèse, Joan of Arc, who died in 1431 but was not canonized until 1920. Thérèse was declared co-patron of the missions with Francis Xavier in 1927, and named co-patron of France with St. Joan of Arc in 1944. On 19 October 1997 Pope John Paul II declared her the thirty-third Doctor of the Church, the only Doctor of his long pontificate, the youngest of all Doctors of the Church, only the third woman Doctor. Devotion to Saint Thérèse has developed around the world.[1]

The depth and novelty of her spirituality, of which she said "my way is all confidence and love," has inspired many believers (see Devotees of St. Thérèse). In the face of her littleness and nothingness, she trusted in God to be her sanctity. She wanted to go to Heaven by an entirely new little way. "I wanted to find an elevator that would raise me to Jesus." The elevator, she wrote, would be the arms of Jesus lifting her in all her littleness.

The Basilica of Lisieux is the second greatest place of pilgrimage in France after Lourdes.[2][3]

Contents |

Life

Family background

Marie-Françoise-Thérèse Martin was born in rue Saint-Blaise, Alençon, France, 2 January 1873, the daughter of Louis Martin, a watchmaker and jeweller , and Zélie Guérin, a lacemaker.[4] Both her parents were devout Catholics. Louis had tried to become a monk, wanting to enter the Augustinian Monastery of the Great St Bernard, but had been refused because he knew no Latin. Zélie, possessed of a strong, active temperament, wished to serve the sick, and had knocked on the door of the Sisters of Charity of St Vincent de Paul[5] — but was rejected because the superior felt she had no vocation to the religious life. Instead, she asked God to give her many children and let them all be consecrated to God.

Louis and Zélie met in 1858 and married only three months later.[6] They had nine children, of whom only five daughters—Marie, Pauline, Léonie, Céline and Thérèse—survived to adulthood. Zélie was so successful in manufacturing lace that Louis sold his watchmaking shop to a nephew and handled the traveling and bookkeeping end of her lacemaking business.

In the six years before Thérèse was born, Zélie Martin faced many challenges in her business and in the health of her children. Her third child, Léonie, suffered convulsions. In 1867 and 1868 her two sons, (Marie-Joseph-Louis and Marie Jean-Baptiste),[7] died at five and eight months old respectively. Meanwhile, she considered herself "a slave to the lace business" and often ran fevers. In 1870, Marie-Hélène, a lovable child of five and a half, also died in Zélie's arms after a painful illness, at a time when there was no vaccination. Marie-Mélanie-Thérèse died an infant, less than two months old, in October 1870. However, Zélie was determined to have one more child and to keep it alive. That last child, the second Thérèse, barely survived but grew to become a saint.[8]

Birth and survival

Soon after her birth in January, the outlook for the survival of Thérèse Martin was very grim. Two weeks after birth she developed an intestinal illness, and Zélie began to see the alarming symptoms she had seen with her other children who died. In March Zélie could no longer nurse the child, and one night the doctor warned her to find a wet nurse if she wanted to save the child.

Since Louis was away on business, the next morning Zélie walked about four miles, often across open farmlands, to beg Rose Taillé to come with her and nurse the child. By the time the two women walked back, Thérèse looked almost dead, but Rose and Zélie managed to save her. Rose had children of her own and could not live with the Martins, so Thérèse was sent to live with Rose in the forests of the Bocage at Semallé — her life saved only by the painful price of separation. When Thérèse was 15 months old, she came home for good. She did not cry, was described as charming and advanced for her age. Before she was three, Thérèse began to read.[10] The mother's humorous letters from this time provide a vivid picture of the baby Thérèse. "My little Thérèse is gentle and sweet as an angel. She has a delightful character; one can see that already. She has such a dear smile." "She is cleverer than any of you were as a baby." And in a letter to Pauline when Thérèse was three; " She is intelligent enough, but not nearly so docile as her sister Céline. When she says no nothing can make her change, and she can be terribly obstinate. You could keep her down in the cellar all day without getting a yes out of her; she would rather sleep there."

On 28 August 1877, Zélie Martin died of breast cancer. Feeling the approach of death Madame Martin had written to Pauline in the spring of that year, "You and Marie will have no difficulties with her upbringing. Her disposition is so good. She is a chosen spirit." Thérèse was barely four and a half years old. Her mother's death dealt her a severe blow. She wrote: "Every detail of my mother's illness is still with me, specially her last weeks on earth." She remembered the bedroom scene where her dying mother received the last sacraments while Thérèse knelt and her father cried. She wrote: "When Mummy died, my happy disposition changed. I had been so lively and open; now I became diffident and oversensitive, crying if anyone looked at me. I was only happy if no one took notice of me... It was only in the intimacy of my own family, where everyone was wonderfully kind, that I could be more myself."[11][12]

Three months after Zélie died, Louis Martin left Alençon, where he had spent his youth and the years of his marriage, and moved to Lisieux in the Calvados Department of Normandy, where Zélie's brother Isidore Guérin, a pharmacist, lived with his wife and two daughters. In her last months Zélie had given up the lace business; after her death, Louis sold it. Louis bought a pretty, spacious country house, Les Buissonnets, situated in a large garden on the slope of a hill overlooking the town. Looking back, Thérèse would see the move to Les Buissonnets as the beginning of the "second period of my life, the most painful of the three: it extends from the age of four-and-a-half to fourteen, the time when I rediscovered my childhood character, and entered into the serious side of life."[13] In Lisieux , Pauline took on the role of Thérèse's Mamma. She took this role seriously, and Thérèse grew especially close to her, and to Céline, the sister closest to her in age.

Early years

Thérèse was taught at home until she was eight and a half, and then entered the school kept by the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre Dame du Pre in Lisieux. The fact that Thérèse, taught well and carefully by Marie and Pauline, was placed in a class of girls several years older than herself, based on her abilities, caused friction with the other students. "Since she could not achieve inconspicuousness by adjustment, and since being conspicuous was embarrassing and shaming to her, Thérèse henceforth deliberately sought the camouflage of retirement. 'She now developed a fondness for hiding' Céline informs us[14] 'she did not want to be observed, for she sincerely considered herself inferior.'"[15] On her free days she became more and more attached to Marie Guérin, the younger of her two cousins in Lisieux. The two girls would play at being anchorites, as the great Teresa had once played with her brother. And every evening she plunged into the family circle. "Fortunately I could go home every evening and then I cheered up. I used to jump on Father's knee and tell him what marks I had had, and when he kissed me all my troubles were forgotten...I needed this sort of encouragement so much." Yet the tension of the double life and the daily self-conquest placed a strain on Thérèse. Going to school became more and more difficult.

When she was nine years old, in October 1882, her sister Pauline who had acted as a "second mother" to her, entered the Carmelite monastery at Lisieux. Thérèse was devastated. She understood that Pauline was cloistered and that she would never come back. "I said in the depths of my heart: Pauline is lost to me !" The shock reawakened in her the trauma caused by her mother's death. She also wanted to join the Carmelites, but was told she was too young. Yet Thérèse so impressed Mother Gonzague the prioress that she wrote to comfort her, calling Thérèse "my future little daughter." In 1886 her oldest sister, Marie, entered the same Carmelite monastery, adding to Therese's grief. The separation from her sisters brought Thérèse a significant amount of suffering. She often feared that her father would die too. She felt alone and wrote: "No one paid any attention to me" but she used her time alone to spend many hours before the Blessed Sacrament. School was difficult for Thérèse : " I have often heard it said that the time spent at school is the best and happiest of one's life. It wasn't so for me. The five years I spent at school were the saddest in my life, and if my dear Céline had not been with me I could not have stayed there for a single month without falling ill."

At this time, Thérèse was often sick; she began to suffer from nervous tremors. The tremors started one night after her uncle took her for a walk and began to talk about Zélie. Assuming that she was cold, the family covered Therese with blankets, but the tremors continued; she clenched her teeth and could not speak. The family called Dr. Notta, who could make no diagnosis.[16] In 1882, Dr Gayral diagnosed that Thérèse "reacts to an emotional frustration with a neurotic attack."[17] An alarmed, but cloistered, Pauline began to write letters to Thérèse and attempted various strategies to intervene. Eventually Thérèse recovered after she had turned to gaze at a statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary and reported on 13 May 1883 that she had seen the Virgin smile at her.[18][19] She wrote: "Our Blessed Lady has come to me, she has smiled upon me. How happy I am".[20] The date 13 May later became a significant Marian date at Our Lady of Fátima, long after Thérèse's death.[21]

Thérèse also suffered from scruples, a condition experienced by other saints such as Alphonsus Liguori, also a Doctor of the Church and Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. She wrote: "One would have to pass through this martyrdom to understand it well, and for me to express what I experienced for a year and a half would be impossible."[22]

Christmas Eve 1886 was a turning point in the life of Therese; she called it her "complete conversion." Years later she stated that on that night she overcame the pressures she had faced since the death of her mother and said that "God worked a little miracle to make me grow up in an instant." Years later she said: "On that blessed night . . . Jesus, who saw fit to make Himself a child out of love for me, saw fit to have me come forth from the swaddling clothes and imperfections of childhood."[23]

The character of the saint and the early forces that shaped her personality have been the subject of analysis, particularly in recent years. Apart from the family doctor who observed her in the 19th century, all other conclusions are inevitably speculative. For instance, author Ida Friederike Görres whose formal studies had focused on church history and hagiography wrote a book that performed a psychological analysis of the saint's character. Some authors suggest that Thérèse had a strongly neurotic aspect to her personality for most of her life.[24][25][26][27].

Imitation of Christ and entry to Carmel

Before she was fourteen, when she started to experience a period of calm, Thérèse started to read The Imitation of Christ. She read the Imitation intently, as if the author traced each sentence for her: "The Kingdom of God is within you... Turn thee with thy whole heart unto the Lord; and forsake this wretched world: and thy soul shall find rest."[28] She kept the book with her constantly and wrote later that this book and parts of another book of a very different character, lectures by Abbé Arminjon on The End of This World, and the Mysteries of the World to Come, nourished her during this critical period.[29] Thereafter she began to read other books, mostly on history and science.[30]

In May 1887, Thérèse approached her 63-year old father Louis, recovering from a small stroke, while he sat in the garden one Sunday afternoon and told him that she wanted to celebrate the anniversary of "her conversion" by entering Carmel before Christmas. Louis and Thérèse both broke down and cried, but Louis got up, gently picked a little white flower, root intact, and gave it to her, explaining the care with which God brought it into being and preserved it until that day. Therese later wrote: "while I listened I believed I was hearing my own story." To Therese, the flower seemed a symbol of herself, "destined to live in another soil". Thérèse then renewed her attempts to join the Carmel, but the priest-superior of the monastery would not allow it on account of her youth.

During the summer, French newspapers were filled with the story of Henri Pranzini, convicted of the brutal murder of two women and a child. To the outraged public Pranzini represented all that threatened the decent way of life in France. In July and August 1887 Thérèse prayed hard for the conversion of Pranzini, so his soul could be saved, yet Pranzini showed no remorse. At the end of August, the newspapers reported that just as Pranzini's neck was placed on the guillotine, he had grabbed a crucifix and kissed it three times. Thérèse was ecstatic and believed that her prayers had saved him. She continued to pray for Pranzini after his death.[31]

In November 1887, Louis took Céline and Thérèse on a diocesan pilgrimage to Rome for the priestly jubilee of Pope Leo XIII. During a general audience with Leo XIII, Therese in her turn approached the pope, knelt, and asked him to allow her to enter at 15. The Pope said: "Well, my child, do what the superiors decide.... You will enter if it is God's Will" and he blessed Thérèse. She refused to leave his feet, and the Swiss Guard had to carry her out of the room.[32]

Soon after that, the Bishop of Bayeux authorized the prioress to receive Thérèse, and on 9 April 1888 she became a Carmelite postulant.

In 1889, her father suffered a stroke and was taken to a private sanatorium, the Bon Sauveur at Caen, where he remained for three years before returning to Lisieux in 1892. He died on 29 July 1894. Upon his death, Céline, who had been caring for him, entered the same Carmel as her three sisters on 14 September 1894; their cousin, Marie Guérin, entered on 15 August 1895. Léonie, after several attempts, became Sister Françoise-Thérèse, a nun in the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary at Caen, where she died in 1941.[33]

The Little Flower in Carmel

Monday 9 April 1888 was the Feast of the Annunciation. That morning, Thérèse took one last look at her childhood home and left for Carmel. She felt peace after she received communion that day and later wrote: "At last my desires were realized, and I cannot describe the deep sweet peace which filled my soul. This peace has remained with me during the eight and a half years of my life here, and has never left me even amid the greatest trials."[34] From her childhood, Thérèse had dreamed of the desert to which God would some day lead her. Now she had entered that desert. Though she was now reunited with Marie and Pauline, from the first day she began her struggle to win and keep her distance from her sisters. Right at the start Marie de Gonzague, the prioress, had turned the postulant Thérèse over to her eldest sister Marie, who was to teach her to follow the Divine Office. Later she appointed Thérèse assistant to Pauline in the refectory. And when her cousin Marie Guerin also entered, she employed the two together in the sacristy. Thérèse adhered strictly to the rule which forbade all superfluous talk during work. She saw her sisters together only in the hours of common recreation after meals. At such times she would sit down beside whomever she happened to be near, or beside a nun whom she had observed to be downcast, disregarding the tacit and sometimes expressed sensitivity and even jealousy of her biological sisters. " We must apologize to the others for our being four under one roof " she was in the habit of remarking. " When I am dead, you must be very careful not to lead a family life with one another..I did not come to Carmel to be with my sisters; on the contrary, I saw clearly that their presence would cost me dear, for I was determined not to give way to nature. "

The final years

Thérèse's final years were marked by a steady decline that she bore resolutely and without complaint. Tuberculosis was the key element of Therese's final suffering, but she saw that as part of her spiritual journey. After observing a rigorous Lenten fast in 1896, she went to bed on the eve of Good Friday and felt a joyous sensation. She wrote: "Oh! how sweet this memory really is!... I had scarcely laid my head upon the pillow when I felt something like a bubbling stream mounting to my lips. I didn't know what it was".

The next morning she found blood on her handkerchief and understood her fate. Coughing up of blood meant tuberculosis, and tuberculosis meant death.[36] She wrote:

"I thought immediately of the joyful thing that I had to learn, so I went over to the window. I was able to see that I was not mistaken. Ah! my soul was filled with a great consolation; I was interiorly persuaded that Jesus, on the anniversary of His own death, wanted to have me hear His first call!"

Thérèse corresponded with a Carmelite mission in what was then French Indochina and was invited to join them, but, because of her sickness, could not travel. In July 1897, she made a final move to the monastery infirmary, where she died on 30 September 1897 at the young age of 24. On her death-bed, she is reported to have said:

"I have reached the point of not being able to suffer any more, because all suffering is sweet to me."

Thérèse was buried in the Carmelite plot in the municipal cemetery at Lisieux, where Louis and Zelie had been buried. In March 1923, however, before she was beatified, her body was returned to the Carmel of Lisieux, where it remains.

Spiritual legacy

At fourteen, Thérèse had understood her vocation to pray for priests, to be "an apostle to apostles." In September 1890, at her canonical examination before she professed her religious vows, she was asked why she had come to Carmel. She answered "I came to save souls, and especially to pray for priests." Throughout her life she prayed fervently for priests, and she corresponded with and prayed for a young priest, Adolphe Roulland, and a young seminarian, Maurice Bellière. She wrote to her sister "Our mission as Carmelites is to form evangelical workers who will save thousands of souls whose mothers we shall be."[3]

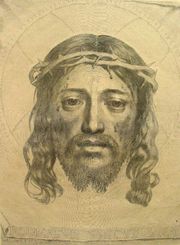

The Child Jesus and the Holy Face

Thérèse entered the Carmelite order on 9 April 1888. On 10 January 1889, after a probationary period somewhat longer than the usual, she was given the habit and received the name: Thérèse of the Child Jesus. On 8 September 1890, Thérèse took her vows; the ceremony of taking the veil followed on the 24th, when she added to her name in religion, "of the Holy Face", a title which was to become increasingly important in the development and character of her inner life.[37] In his "A l'ecole de Therese de Lisieux: maitresse de la vie spirituelle," Bishop Guy Gaucher emphasizes that Therese saw the devotions to the Child Jesus and to the Holy Face as so completely linked that she signed herself "Therese de l'Enfant Jesus de la Sainte Face"--Therese of the Child Jesus of the Holy Face. Unlike most religious who had two such titles, she did not link them with "and." In her poem "My Heaven down here", composed in 1895, Therese expressed the notion that by the divine union of love, the soul takes on the semblance of Christ. By contemplating the sufferings associated with the Holy Face of Jesus, she felt she could become closer to Christ.[38]

The devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus was promoted by another Carmelite nun, Sister Marie of St Peter in Tours, France in 1844 and then by Leo Dupont, also known as the Apostle of the Holy Face who formed the "Archconfraternity of the Holy Face" in Tours in 1851.[39][40] Thérèse, who was a member of this confraternity,[41] was introduced to the Holy Face devotion by her blood sister Pauline, known as Sister Agnes of Jesus.

Her parents, Louis and Zelie Martin, had also prayed at the Oratory of the Holy Face, originally established by Leo Dupont in Tours.[42] Thérèse wrote many prayers to express her devotion to the Holy Face. She wrote the words "Make me resemble you, Jesus!" on a small card and attached a stamp with an image of the Holy Face. She pinned the prayer in a small container over her heart. In August 1895, in her "Canticle to the Holy Face," she wrote:

"Jesus, Your ineffable image is the star which guides my steps. Ah, You know, Your sweet Face is for me Heaven on earth. My love discovers the charms of Your Face adorned with tears. I smile through my own tears when I contemplate Your sorrows".

Thérèse emphasised God's mercy in both the birth and the passion narratives in the Gospel. She wrote:[43]

"He sees it disfigured, covered with blood!... unrecognizable!... And yet the divine Child does not tremble; this is what He chooses to show His love."

She also composed the Holy Face prayer for sinners:[44]

"Eternal Father, since Thou hast given me for my inheritance the adorable Face of Thy Divine Son, I offer that face to Thee and I beg Thee, in exchange for this coin of infinite value, to forget the ingratitude of souls dedicated to Thee and to pardon all poor sinners."

Thérèse's devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus was based on painted images of the Veil of Veronica, as promoted by Leon Dupont fifty years earlier. However, over the decades, her poems and prayers helped to spread the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus.[45]

The Little Way

.jpg)

In her quest for sanctity, she believed that it was not necessary to accomplish heroic acts, or "great deeds", in order to attain holiness and to express her love of God. She wrote,

"Love proves itself by deeds, so how am I to show my love? Great deeds are forbidden me. The only way I can prove my love is by scattering flowers and these flowers are every little sacrifice, every glance and word, and the doing of the least actions for love."

This little way of Therese is the foundation of her spirituality:[46] Within the Catholic Church Thérèse's way was known for some time as "the little way of spiritual childhood," but Thérèse actually wrote "little way" only once,[47] and she never wrote the phrase "spiritual childhood." It was her sister Pauline who, after Thérèse's death, adopted the phrase "the little way of spiritual childhood" to interpret Thérèse's path.[48] Years after Thérèse's death, a Carmelite of Lisieux asked Pauline about this phrase and Pauline answered spontaneously "But you know well that Thérèse never used it! It is mine." In May 1897, Thérèse wrote to Father Adolphe Roulland, "My way is all confidence and love." To Maurice Bellière she wrote "and I, with my way, will do more than you, so I hope that one day Jesus will make you walk by the same way as me."

"Sometimes, when I read spiritual treatises in which perfection is shown with a thousand obstacles, surrounded by a crowd of illusions, my poor little mind quickly tires. I close the learned book which is breaking my head and drying up my heart, and I take up Holy Scripture. Then all seems luminous to me; a single word uncovers for my soul infinite horizons; perfection seems simple; I see that it is enough to recognize one's nothingness and to abandon oneself, like a child, into God's arms. Leaving to great souls, to great minds, the beautiful books I cannot understand, I rejoice to be little because 'only children, and those who are like them, will be admitted to the heavenly banquet'."

Passages like this have left Thérèse open to the charge that her spirituality is sentimental, immature, and unexamined. Her proponents counter that she developed an approach to the spiritual life that people of every background can understand and adopt.

This is evident in her approach to prayer:[49]

"For me, prayer is a movement of the heart; it is a simple glance toward Heaven; it is a cry of gratitude and love in times of trial as well as in times of joy; finally, it is something great, supernatural, which expands my soul and unites me to Jesus. . . . I have not the courage to look through books for beautiful prayers.... I do like a child who does not know how to read; I say very simply to God what I want to say, and He always understands me."

Autobiography – "The Story of a Soul"

St. Thérèse is known today because of her spiritual memoir, L'histoire d'une âme ("The Story of a Soul"), which she wrote upon the orders of two prioresses of her monastery, and because of the many miracles worked at her intercession. She began to write "Story of a Soul" in 1895 as a memoir of her childhood, under instructions from her sister Pauline, known in religion as Mother Agnes of Jesus. Mother Agnes gave the order after being prompted by their eldest sister, Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart. While Thérèse was on retreat in September 1896, she wrote a letter to Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart which also forms part of what was later published as "Story of a Soul." In June 1897, Mother Agnes became aware of the seriousness of Thérèse's illness; she immediately asked Mother Marie de Gonzague, who had succeeded her as prioress, to allow Thérèse to write another memoir with more details of her religious life. With selections from Therese's letters and poems and reminiscences of her by the other nuns, it was published posthumously. It was heavily edited by Pauline (Mother Agnes), who made more than seven thousand revisions to Therese's manuscript and presented it as a biography of her sister. (Aside from considerations of style, Mother Marie de Gonzague had ordered Pauline to alter the first two sections of the manuscript to make them appear as if they were addressed to Mother Marie as well).

Since 1973, two centenary editions of Thérèse's original, unedited manuscripts, including "Story of a Soul," her letters, poems, prayers and the plays she wrote for the monastery recreations have been published in French. ICS Publications has issued a complete critical edition of her writings: "Story of a Soul," "Last Conversations," and the two volumes of her letters were translated by John Clarke, O.C.D.; "The Poetry of Saint Thérèse" by Donald Kinney, O.C.D.; and "The Prayers of St. Thérèse" by Alethea Kane, O.C.D.; and "The Religious Plays of St. Therese of Lisieux," by David Dwyer and Susan Conroy.

Recognition

Canonization

In 1902, the Polish Carmelite Father Raphael Kalinowski (later Saint Raphael Kalinowski) translated her autobiography "Story of a Soul" into Polish.

Her autobiography has inspired many people, including the Italian writer Maria Valtorta.

Pope Pius X signed the decree for the opening of her process of canonization on 10 June 1914. Pope Benedict XV, in order to hasten the process, dispensed with the usual fifty-year delay required between death and beatification. On 14 August 1921, he promulgated the decree on the heroic virtues of Thérèse and gave an address on Thérèse's way of confidence and love, recommending it to the whole Church.

There may, however, have been a political dimension to the speed of proceedings: partly to act as tonic for a nation exhausted by war, or even a retort from the Vatican against the dominant secularism and anti-clericalism of the French government.

According to some biographies of Edith Piaf, in 1922 the singer — at the time, an unknown seven-year-old girl — was cured from blindness after pilgrimage to the grave of Thérèse, at the time not yet formally canonised.

Thérèse was beatified on 29 April 1923 and canonized on 17 May 1925, by Pope Pius XI, only 28 years after her death. Her feast day was added to the Roman Catholic calendar of saints in 1927 for celebration on 3 October.[50] In 1969, 42 years later, Pope Paul VI moved it to 1 October, the day after her dies natalis (birthday to heaven).[51]

Thérèse of Lisieux is the patron saint of people with AIDS, aviators, florists, illness(es) and missions. She is also considered by Catholics to be the patron saint of Russia, although the Russian Orthodox Church does not officially recognize either her canonization or her patronage. In 1927, Pope Pius XI named Thérèse a patroness of the missions and in 1944 Pope Pius XII named her co-patroness of France alongside St. Joan of Arc.

By the Apostolic Letter Divini Amoris Scientia ("The Science of Divine Love") of 19 October 1997, Pope John Paul II declared her one of the thirty-three Doctors of the Universal Church, one of only three women so named, the others being Teresa of Avila (Saint Teresa of Jesus) and Catherine of Siena. Thérèse was the only saint to be named a Doctor of the Church during Pope John Paul II's pontificate.

A movement is now under way to canonise her parents, who were declared "Venerable" in 1994 by Pope John Paul II. In 2004, the Archbishop of Milan accepted the unexpected cure of a child with a lung disorder as attributable to their intercession. Announced by Cardinal Saraiva Martins on 12 July 2008, at the ceremonies marking the 150th anniversary of the marriage of the Venerable Zelie and Louis Martin, their beatification as a couple [4] (the last step before canonization) took place on Mission Sunday, 19 October 2008, at Lisieux.[52][53] Some interest has also been shown in promoting for sainthood Thérèse's sister, Léonie, the only one of the five sisters who did not become a Carmelite nun. Léonie Martin, in religion Sister Françoise-Thérèse, died in 1941 in Caen, where her tomb in the crypt of the Visitation Monastery can be visited by the public.

Together with St. Francis of Assisi, St. Thérèse of Lisieux is one of the most popular Catholic saints since apostolic times. As a Doctor of the Church, she is the subject of much theological comment and study, and, as a seemingly appealing young woman whose message has touched the lives of millions, she remains the focus of much popular devotion.

Relics of St. Thérèse on a world pilgrimage

For many years Thérèse's relics have toured the world, and thousands of pilgrims have thronged to pray in their presence. Although Cardinal Basil Hume had declined to endorse proposals for a tour in 1997, her relics finally visited England and Wales in late September and early October 2009, including an overnight stop in the Anglican York Minster on her feastday, 1 October. A quarter of a million people venerated them.[54]

On 27 June 2010, the relics of St. Thérèse are to make their first visit to South Africa in conjunction with the 2010 World Cup. They will remain in the country until 5 October 2010.[55]

Religious congregations

The Congregation of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux was founded on 19 March 1931 by Mar Augustine Kandathil, the Metropolitan of the Catholic St. Thomas Christians, as the first Indian religious order for brothers.[56]

Places named after St. Thérèse

A number of locations, churches, and schools throughout the world are named after Saint Thérèse.

The Basilica of St. Thérèse in her home town of Lisieux was consecrated on 11 July 1954; it has become a centre for pilgrims from all over the world. It was originally dedicated in 1937 by Cardinal Pacelli, later Pope Pius XII. The basilica can seat 4,000 people.[57].

Devotees of St. Thérèse

Over the years, a number of prominent people have become devotees of St. Thérèse. These include:

- Albino Luciani – Pope John Paul I

- Henri Bergson – Nobel prize winner

- Padre Pio – Italian saint

- Ada Negri – Italian poet

- Giuseppe Moscati – Italian saint

- Maria Valtorta – Catholic mystic

- Francis Bourne – British Cardinal

- Thomas Merton – monk and writer

- Dorothy Day – founder of the Catholic Worker movement

- Georges Bernanos – French author

- Jack Kerouac – American author

- St. Maximilian Kolbe – Polish martyr of Auschwitz

- Jean Vanier – founder of l'Arche

Bibliography

- Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0

- Thérèse of Lisieux: the way to love by Ann Laforest, 2000 ISBN 1-58051-082-5

- The Story of a Soul by T. N. Taylor, 2006 ISBN 1-4068-0771-0

- Thérèse of Lisieux by Joan Monahan, 2003 ISBN 0-8091-6710-7

- Thérèse of Lisieux: God's gentle warrior by Thomas R. Nevin, 2006 ISBN 0-19-530721-6

- Therese and Lisieux by Pierre Descouvemont, Helmuth Nils Loose, 1996 ISBN 0-8028-3836-7

- St. Thérèse of Lisieux: a transformation in Christ by Thomas Keating, 2001 ISBN 1-930051-20-4

- Thérèse of Lisieux: Through Love and Suffering, by Murchadh O Madagain, 2003 ISBN

See also

- Carmelite Rule of St. Albert

- Book of the First Monks

- Constitutions of the Carmelite Order

- Byzantine Discalced Carmelites

- Secular Order of Discalced Carmelites

- National Shrine of the Little Flower

References

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: God's gentle warrior by Thomas R. Nevin, 2006 ISBN 0-19-530721-6 page 26

- ↑ Vatican website: Proclamation as Doctor of the Church

- ↑ CatholicForum.com: Patron Saints Index: Thérèse of Lisieux Retrieved on 1 October 2006

- ↑ Venerable and to-be-Blessed Zelie and Louis Martin: Their Lives

- ↑ The Hidden Face p.38 Ida Görres

- ↑ The medallion Louis gave to Zélie during their wedding ceremony Saint Therese of Lisieux: A Gateway

- ↑ The Spiritual Journey of St Thérèse of Lisieux p.227 ISBN 0 232 51713 4

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 page 9

- ↑ Ida Gorres, The Hidden Face p.41-42

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 pages 9–12

- ↑ Ordinary Suffering of Extraordinary Saints by Vincent J. O'Malley, 1999 ISBN 0-87973-893-6 page 38

- ↑ The Hidden Face p. 66

- ↑ Guy Gaucher The Spiritual Journey of Therese of Lisieux

- ↑ Summarium 1 1914

- ↑ The Hidden Face , Ida Gorres p.73

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 page 19

- ↑ Pierre Descouvemont and Helmuth Nils Loose, "Therese and Lisieux", p. 53, Toronto, 1996

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 page 22

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: the way to love by Ann Laforest, 2000 ISBN 1-58051-082-5 page 15

- ↑ The Story of a Soul by T. N. Taylor, 2006 ISBN 1-4068-0771-0 page 32

- ↑ Our Sunday Visitor's encyclopedia of saints by Matthew Bunson 2003 ISBN 1-931709-75-0 page 418

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux by Joan Monahan, 2003 ISBN 0-8091-6710-7 page 45

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux by Joan Monahan, 2003 ISBN 0-8091-6710-7 page 54

- ↑ Ida Friederike Görres, "The hidden face: a study of St. Thérèse of Lisieux", p. 83, London, 2003

- ↑ Karen Armstrong, "The Gospel according to woman: Christianity's creation of the sex war in the West", p. 234, London, 1986

- ↑ Monica Furlong Thérèse of Lisieux, p.9, London, 2001

- ↑ Jean François Six, La verdadera infancia de Teresa de Lisieux: neurosis y santidad, passim, Spain, 1976

- ↑ The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, 2003 Dover Press ISBN 0-486-43185-1

- ↑ Ida Gorres, The Hidden Face p. 126-127

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 page 22

- ↑ Thérèse of Lisieux: a biography by Patricia O'Connor, 1984 ISBN 0-87973-607-0 page 34

- ↑ Phyllis G. Jestice, Holy people of the world Published by ABC-CLIO, 2004 ISBN 1-57607-355-6

- ↑ Clarke, John O.C.D. trans. The Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus, 3rd Edition (Washington DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1996)

- ↑ The Story of a Soul by T. N. Taylor, 2006 ISBN 1-4068-0771-0 page 63

- ↑ The Photo Album of St. Therese of Lisieux; commentary, Francois de Sainte-Marie, O.C.D.; translator, Peter-Thomas Rohrbach, O.C.D. New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons, 1962, p. 145.

- ↑ The making of a social disease: tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France by David S. Barnes 1995 ISBN 0-520-08772-0 page 66

- ↑ Ida Friederike Gorres p.164 The Hidden Face ISBN 0-89870-927-X

- ↑ Thomas R. Nevin, Thérèse of Lisieux: God's gentle warrior Oxford University Press US, 2006 ISBN 0-19-530721-6 pages 184 and 228

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Reparation

- ↑ Dorothy Scallan, The Holy Man of Tours (1990) ISBN 0-89555-390-2

- ↑ Therese joined this confraternity on April 26, 1885. See Derniers Entretiens, Desclee de Brouwer/Editions Du Cerf, 1971, Volume I, p. 483

- ↑ Paulinus Redmond, 1995 Louis and Zelie Martin: The Seed and the Root of the Little Flower Cimino Press ISBN 1-899163-08-5 page 257

- ↑ Ann Laforest, Thérèse of Lisieux: the way to love Published by Rowman & Littlefield, 2000 ISBN 1-58051-082-5 page 61

- ↑ Catholic.org

- ↑ Pierre Descouvemont, Thérèse and Lisieux Eerdmans Publishing, 1996 ISBN 0-8028-3836-7 page 137

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Clarke, John O.C.D. trans. The Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus, 3rd Edition (Washington DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1996, p. 207).

- ↑ "The Power of Confidence: Genesis and Structure of the "Way of Spiritual Childhood" of St. Therese of Lisieux. Staten Island, NY: Alba House (Society of St. Paul), 1988, p. 5

- ↑ Therese's prayer

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 104

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 141

- ↑ "Béatification à Lisieux des parents de sainte Thérèse" (in French). L'essemtiel des saints et des prénoms. Prenommer. 19 October 2008. http://www.prenommer.com/a-la-une-paris/beatification-a-lisieux-des-parents-de-sainte-therese/. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "God's Word renews Christian life". l'Osservatore Romano (Holy See). 22 October 2008. http://www.vatican.va/news_services/or/or_eng/043w01.pdf. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ Tens of Thousands Flock to St. Thérèse Relics, By Anna Arco, 25 September 2009, The Catholic Herald (UK) [2]

- ↑ http://www.thereseoflisieux.org/st-thereses-relics-visit-south/

- ↑ Fr. George Thalian: The Great Archbishop Mar Augustine Kandathil, D. D.: the Outline of a Vocation, Mar Louis Memorial Press, 1961. (Postscript) (PDF)

- ↑ Saint-Theres.org

External links

- Web site of the Pilgrimage Office at Lisieux

- Web site about the life, writings, spirituality,and mission of Saint Therese of Lisieux

- Sainte Thérèse de Lisieux, biographie

- The Story of a Soul (L'Histoire d'une Âme): The Autobiography of St. Thérèse (early edition heavily edited by Thérèse's sister)

- http://www.saintetherese.org (Sainte Thérèse – Mansourieh / Liban) Parish site in the Lebanese language

- Official web site of the full-length feature film on the life of St. Thérèse of Lisieux

- Pope John Paul II's Divini Amoris Scientia in English

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Works by Thérèse de Lisieux at Project Gutenberg early 20th century editions, heavily edited by Therese's sister

- Second Class Relic of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

- Saint Thérèse Memorial Page at FindaGrave

- St. Thérèse's relics at Hungary

- A collection of pictures of Thérèse, on the Lisieux Sanctuary website

|

|||||